As demand for French cheese soars in the Middle East, Catering News visits the cheese-making regions of the east of France to explore the traditions, techniques and talent behind some of the country’s best-love varieties.

While consumption of French cheese in the region is at an all-time high, many chefs and consumers are unaware of the amount of work that goes into producing French cheese – from the milking to the curd cutting and shaping to the aging process – and the best ways to store and enjoy cheese products. To find out more, Catering News took a trip to the French regions of Franche Comte and Rhone-Alps, visiting some of the farms, cheese producers and agers working hard to maintain the heritage and quality of the cheese produced in their areas. The trip was led by award-winning French cheesemonger Francois Robin, who holds the title of ‘Un des Meilleurs Ouvriers de France’ (One of the Best Craftsmen of France) a unique and prestigious award, according to a category of trades in a contest among professionals – one of which is cheesemongers. He explains: “Behind each French cheese, there is a link to the grass. Farms are small with the average size 45 – 60 cows. Any time you buy a French cheese, a lot of work goes into it, from milking to making the cheese, aging it and shipping it.”

Taking us on a journey exploring the full cycle of cheese production, Robin first showed us the importance of terroir for producing quality milk – the foundation of any good cheese. The terroir differs from region to region and from farm to farm. We visited two different farms, the first being Ferme Du Beau Pre in Champagnole, run by Dominique Faivre. The organic farm boasts 100 hectares of natural pastures, cereals and hay fields, which are necessary for the production of Comté since no fermented food is allowed. All on one pasture, the farm is surrounded by water on each side, creating a natural barrier against external chemicals. Just 45 cows are milked here all year round, producing 250,000 litres of milk per annum – well below the farm’s quota of 400,000 litres. By controlling the number of cows on the farm, Faivre keeps costs down and ensures the farm is sustainable for future generations and that the animals are happy, which is essential for producing good quality milk.

“There is a really low stress level for the animals and you can hear that,” says Faivre, pointing out the quietness of the barn as the cows are milked. The milk is collected twice a day by the local Comté PDO maker (Fruitiere) and all of it goes toward making the cheese.

We also took a trip to Ferme des Peizieres in Le Bouchet Mont Charvin, a beautiful farm set in the scenic heights of the French Alps. Run by a young couple, 27-year-old Mathilde and 25-year-old Fabrice, the farm produces PDO Reblochon, a cheese made from raw cow’s milk. There are just 25 cows of three breeds – the Montbéliarde from Jura, the Abondance and the Tarine – and every ounce of milk is used for making the cheese.

The lifestyle of this ambitious pair isn’t easy, however; Fabrice is up at 4am every morning and rarely gets to bed before 10pm. Milking takes place twice a day – once in the morning and again in the evening – with Mathilde taking charge of producing the cheese daily. Fabrice explains that the bacteria from the grass and the land goes into the cow’s body and studies have shown that the bacteria from this side of the mountain is different to that on the other side, highlighting the strong link between the cheese and the terroir.

The Reblochon is made from room-temperature raw milk, which comes directly from the cows. The first thing Mathilde does is inject more bacteria into the raw milk, since the fresh product is “too clean”. The good bacteria grow at an optimal temperature of 23°C and live off the milk, producing enough acidity to ward off bad bacteria in the cheese.

The milk takes 45 minutes to coagulate and once this process is complete, Mathilde uses a traditional tool to cut the curd and separate the fat and sugar from the whey, which is fed to the animals and used to make butter. It’s also important that the couple stick to making the cheese using the traditional tools, such as the cheese cloth. “When you’re making farmhouse Reblochon you have to do it the traditional way,” says Mathilde. “It’s also useful to prepare the rind because at the start you get a lot of grains and then they become smoother because of the cloth, which helps to give the Reblochon its look and shape.”

The methods being used by Mathilde and Fabrice are very different to those used in the big factories where French cheese is mass produced and exported in bulk. To get a better understanding of the difference in techniques, we visited the Bressor factory, which belongs to Savencia, the second biggest milk and cheese producer in France. Formerly named Bongrain, the company collects milk from 276 farms in the vicinity and produces brands such as Caprice des Dieux, Tartare and Bresse Bleu using state-of-the-art machinery, and exports its products globally, including to Dubai.

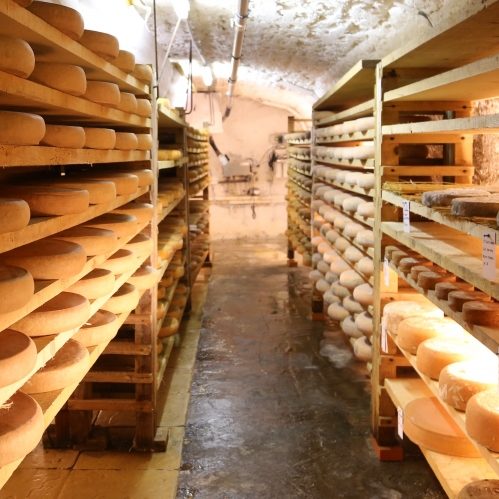

After getting an insight into the milk collection and cheese production processes, we turned our attention to affinage, or aging. There are affineurs all over the region, with some located in scenic mountain chalets and others in city centres – we visited both.

Our first stop was Fromagerie Janin in Champagnole, which has been passed down through six generations. The shop sells a huge array of cheeses and contains hidden caves underground, which are used mainly to age Morbier and some Comté – a staple of the Jura region. The family were cheese makers until 1960 before they decided to be solely cheesemongers and affineurs. Robert Janin, now 67, still works every day in the shop and his sons Marc and Matthieu run the business.

Again, it’s not an easy life, with a 5am start and 8.30pm finish each day, and just a one-day weekend if anything. Janin’s speciality is Morbier, and not a lot of cheesemongers do this. There is a smell of ammonia in the caves, but this is a natural gas produced from the cheeses and it isn’t dangerous. The Morbier cheeses are ripened from 45 – 145 days at the most, and each wheel is around five kilos in weight and requires 30 litres of milk. The cheese first came into existence as a way of using up all the milk on the farms after Comté had been produced.

Matthieu explains: “After the Comté had been produced there was still some milk left on the farms, which was enough to make a flat cheese. It was too flat to be left a long time so they would add some ash to prevent fermentation or bugs and the next day they would add the other piece of cheese on top and press it together. The two layers of cheese are separated by a layer of ash and today this is medical ash, which is completely harmless.”

The Comté on the other hand, is not aged from scratch at Janin, but is pushed a little further. The shop sells three varieties – Compé PDO Fruité, aged 18 months, Très Fruité (24 months) and a Comté PDO Réserve (aged 36 months). While around 5% of the cheese aged in the cave is distributed to restaurants in France, 95% is sold in the shop upstairs. In addition to the Comté and Morbier PDO, we got a chance to try Tomme Cironnée, Tomme au Vin Jaune, Bleu de Gex PDO and Cancoillote.

An interesting point to note is that the affineurs (cheese agers) each work differently and all are in pursuit of the right taste, which doesn’t necessarily correspond to the longest duration of aging. There are around 150 cheese producers in Jura and Janin works with just 15, but the challenge is that the cheeses produced each day taste different so getting the right product could mean selecting from 100,000 wheels.

“It takes time and a lot of knowledge and experience,” explains Matthieu. “We spend 20 days a year just selecting the Comté. We go to different affineurs and it’s like selecting wine – we taste the cheese and think about how it will be in six months because that’s when we need it, but the difference is that wine only has one production each year, whereas for cheese it’s one production every day.”

To find out more about the complex task of cheese aging, we visited the revered Mr Jean-Charles Arnaud, whose father created the independent cheese dairy, Juraflore, in Fort des Rousses. Located just 1km from Switzerland, the fort was built under Napolean rule over 70 years by 300 stone makers and was to act as a refuge for 2,000 horses and 3,000 soldiers in case of a siege. The fort was later turned into a cheese affinage facility using its natural temperature and humidity, and today, with the cooperation of 400 livestock farmers and milk producers, 200,000 rounds of cheese – including 140,000 wheels of Comté – are maturing in 10 kilometres of cellars.

Catering News was taken on a guided tour of the enormous fort, which spans seven floors. Each cave has a slightly different environment and we were privileged enough to be allowed access to Mr Arnaud’s prized new cave, which isn’t open to the public. The art of the affineur is to raise cheeses to perfection and in Juraflore there are just five cave masters, each tasked with identifying the perfect time to release the cheeses.

Mr Arnaud explains that in Fort des Rousses, the cheeses are matured for a minimum of one year and this process begins with five weeks in a cellar at 12°C and three weeks at 15-18°C to allow the lactic bacteria inside the cheese and on the surface to grow.

“At this point we can taste the cheese and check the texture and we decide at what point it will be at its best – whether it’s one year, 18 months or two years,” explains Mr Arnaud. After the initial decision is made, the cheese masters revisit each cheese every three months to reconfirm their decisions. Mr Arnaud demonstrates how he tests each cheese with a small hammer, listening carefully to the sound created by each blow to identify how the fat materials and proteins are behaving inside. It is a complex and highly skilled art, which takes at least seven years’ training to master. “I have to decide whether to put the Comté in a reserve cave with more or less ammonia or with a higher level of culture or a humidity because this is the way to select the microflora on the surface and transform the texture and flavour,” he adds.

Another cheese ager in the expansive, mountainous countryside is Paccard Affineurs in Manigod where we met with Eric Favre. Created by Joseph Paccard, the caves are now run by his sons Benoit and Jean-Francois, who took over just recently, and they are used to age the best Reblochon selected from the area, serving 900 customers worldwide. Every day, the cheeses are flipped and tested and aging takes a minimum of 45 days. In addition to Reblochon, Paccard ages Manigodine (similar to Reblochon but aged in wood) and some other tommes, including Tomme de Savoie PGI and Tomme des Bauges PDO. We also tasted Abondance PDO, Mountain Beaufort PDO and Manigodine.

We also visited some city-centre caves, such as Fromagerie Gay in Annecy, run by Pierre Gay, who was awarded the title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France in 2011. Pierre Gay is a second-generation cheesemonger whose shop has a cave underneath with a glass ceiling so that visitors can see the cheeses below. Gay explains that part of his job is to ensure his cheeses look good so that his regular visitors don’t always see the same cheese in the same places. This is with the exception of Comté, which must always remain on display as a staple of the region.

His caves are not purely for aging, since he sells fresh cheese too and works with other producers to age his cheeses, including Mr Arnaud at Juraflore with whom he has worked for 20 years. He says: “I prefer selecting the cheese from the farmers or the small factories and asking them to do the aging for me. Every month we pay about 20 cents for the aging of the cheese so it’s better to sell young cheese than very old cheese because it’s less expensive of course.”

Among the cheeses aged in the facility are Reblochon PDO, Charolais PDO (a goat’s cheese), Beaufort PDO, Tomme des Bauges PDO, and Comté PDO (36 months and 48 months). Gay also demonstrated simple dessert recipes that can be created using French cheese including Fontainebleu, a traditional fresh dairy dessert and mousse au chocolat.

Another city stop was Christan Janier Affineur in Lyon, where Tomme Boudaine, Fourme de Rochefort Montagne, Mountain Beaufort PDO, Truffle Manchego PDO (Spain) and Swiss Gruyere are aged. Janier is a third-generation affineur and has worked with the same producers for a long time, aging more than 100 cheeses in his caves. Of 39 wholesalers that once operated in Lyon, Janier is just one of five left in the city and is thankful to his father for this. “In the 1970s, my father could have done the easy thing and gone into mass production and followed that trend but he said that he wanted to stick with his small farmhouse and production” says Janier.

And while his grandfather aged mostly local products, Janier ages cheeses from around Europe, including Spain, the UK and the Netherlands. However, he is mindful of the importance of terroir with all his cheeses and makes sure to stick to the rules to ensure a quality affinage. “Certain cow breeds are necessary due to the laws of PDO and the hand of the cheesemaker is important,” he comments. “It’s all about the terroir and it’s important to respect that.”

Rounding off the trip, we paid a visit to the famous Halles Paul Bocuse in Lyon, where we visited four cheesemongers – Mons, a high quality affineur in Roanne, which has products available in Dubai; Beillevaire, which offers cheeses and artisan dairy products available in Dubai; Cellerier, which has St Marcellin with Black Truffle and Mère Richard, the creator of St Marcellin a la Lyonnaise. We also had the pleasure of meeting Etienne Boissy, Meilleur Ouvrier de France (MOF) 2004, who worked for 10 years with Hervé Mons, the creator of the Mons brand and MOF 2000. We conducted an extensive cheese tasting with Buchette de Manon (round fresh goat’s cheese), St Nectaire Farmhouse PDO, Salers PDO, home-made basil brie and 1924 (blue cheese).

And so, as the Middle East continues to import cheese in growing quantities, it is important to be mindful of the history, terroir and hard work behind each and every French cheese. Suppliers of French cheeses in the Middle East region include Classic Fine Foods, Promart, Fresh Express, Greenhouse and Lactilis, many of whom can offer in-depth knowledge and information on their products and advice on storage and preparation.

When it comes to selecting French cheeses, our tour-guide Robin advises starting with the PDO varieties. He says: “If a chef doesn’t really know what to buy for a French cheese selection, it’s good to start with the PDO cheeses – there are 45 of them and the label means the cheese has certain qualities. For example, PDO cheeses are Comté, Reblochon and Camembert from Normandy. PDO cheeses are normally a bit more expensive but you can promote them better because there’s a strong link between the terroir and the cheese.”

He reminds us that storage is extremely important for cheese, and chefs are best to buy in small quantities rather than keeping a big stock that can go off. “You’ve got to trust the suppliers – they should know where the cheese comes from and should be able to prove it. If you want to check a cheese has been correctly stored, the rind must look even and shouldn’t have cracks.

“If the cheese is hot after being transported, don’t accept it. It needs to be refrigerated most of the time, so the cold chain is key as well. If you can trust a supplier for the rest of the products, hopefully you can trust them when it comes to cheese.”